Women seeking jobs as domestic workers in the UAE allege they are being detained and abused in squalid accommodation, while recruiters sell them over apps and social media platforms to household employers, according to interviews and documents seen by the Guardian.

In a series of interviews conducted over several years, 14 women from east Africa and the Philippines recounted their experiences with recruitment agencies, including alleging they were denied food, held captive and treated violently.

The Guardian has also seen evidence that the women are being marketed in an “exploitative” way reminiscent of slavery, according to one expert, with employers charged less for the services of black domestic workers and being told they do not even need to provide them with proper bedrooms.

The women’s testimony gives a rare insight into what life is like in domestic worker agency accommodation as migrants wait, in limbo, for an employer to take them on. It is a process that can take months, with women often being returned to the agencies at the whim of an employer.

“The moment we landed [agency staff] took our passports. Then we went to this house. In one little room, eight or nine of us slept. Using mobile phones wasn’t allowed,” says Margarita*, a Filipina who was recruited by an agency in the Emirate of Ajman. “We lie together on the floor until someone buys us.”

Those interviewed were all recruited for work in the UAE in their home countries, some by members of their communities acting as brokers and others by responding to adverts on Facebook. Many expected to be placed immediately with an employer when they reached Dubai. Instead, they were locked in their agency’s accommodation for up to several months without earning a salary to support their families back home.

Angelica Pine, 28, was held for four months by an agency in 2019. She claims she was violently assaulted by a female member of staff.

“She has a bad temper. She kicked me, threw me in her room, pulled my hair, slapped my face, and also she took my personal things like my mobile phone,” says Pine.

The Guardian has spoken to some of these women for up to three years. Some have now made it back to their home countries, after receiving repatriation assistance from their embassies, and are able to give their testimony on their experiences. However, several say they personally know other women who are trapped in recruitment agency accommodation.

Mary*, 34, from Kenya, is stuck in the UAE and told the Guardian she wants to leave her employer. She is exhausted from working more than 18 hours each day, with no day off, for a salary equivalent to $327 (£270) a month. She alleges the employers she was placed with installed cameras in her bedroom, and she says it is difficult to change clothes because she knows they can see her. She asked her recruiters for help to leave but says they accused her of “creating drama”.

“I am still afraid of the agency because I am still under them,” says Mary, who was not given a contract before starting her job. “We are suffering.”

UAE recruitment agencies routinely advertise the women they are holding for sale online. The Guardian has located dozens of these adverts on Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, where women’s photos are displayed, alongside their personal information, where prospective buyers leave comments on the pages and inquire about prices.

All of these adverts were posted by recruitment agencies that had been awarded a licence to operate from the UAE government, and are supposedly certified as companies that protect the rights of the employers and domestic workers.

“The staff force you to put on a hijab, then they film a video of you,” says Nia, 27, from Kenya. “If someone likes your profile, they come to the office, and you do a live interview. You have no option; you need a job.” Nia ultimately spent three months locked in a compound in Dubai that her agency used to hold women in 2021.

Maids.cc, a licensed recruitment agency, has an app and website from where people can select, order and pay for a maid without even meeting her first.

“Get a full-time maid or a maid visa online in 5 minutes. Cancel anytime,” the website states. “You get the maid on the same day. View maids’ videos and hire your favourite. We’ll Uber her to you on the same day.”

It further promotes the convenience of its services on its frequently asked questions page: “Zero legal liability. Maid stays on our visa, so you’ll never have to worry about any legal consequences. If anything goes wrong (eg runaway maid, pregnancy), we’re responsible to deal with any lawsuits or visits to police stations, not you.”

The monthly prices users pay per maid are according to race, the website states – with employers charged less for the services of a black maid. “Filipinas AED3,500 ($952)/month” and “Africans AED2,700 ($735)/month,” it states, but does not disclose the amount of the payment that is actually received by the maid in salary.

after newsletter promotion

The working and living conditions afforded to maids are also decided by race. The website states that Filipina maids require a bedroom of their own to sleep in, while African maids do not.

“It’s hard to know where to start: is the worst thing pricing humans by their race and nationality, promising to deliver a woman to your house by Uber same-day delivery, or claiming that African employees do not need bedrooms?” says James Lynch, co-director of FairSquare, a human rights nonprofit organisation, after reviewing the matters presented to him by the Guardian.

“Demeaning, commodifying and exploiting people like this recalls the trade in enslaved people, conducted online rather than at physical markets,” says Lynch.

Separately, another agency, Leadership Tadbeer (sometimes known as Tadbeer WTC), in Abu Dhabi, advertises maids on TikTok and Instagram. On Instagram, the women advertised are from Indonesia, Ethiopia and Sri Lanka. Their services are being sold for between AED1,100 and AED1,400 a month.

“The practice of advertising domestic workers based on national origin with their personal details has long been a practice in the UAE,” says Rothna Begum, of Human Rights Watch. “This shows how little the authorities are doing to protect domestic workers rights.”

A spokesperson for Leadership Tadbeer said: “Regarding the issue you highlighted, here in the UAE our minister of human resources has organised the relationship between the sponsor, worker and agents.

“Regarding the salary, don’t forget there is also free accommodation, free food, free personal staff, phone allowance and good health insurance. You can see here in UAE, more than 200 nationalities live together safely. Everyone here respects each other.”

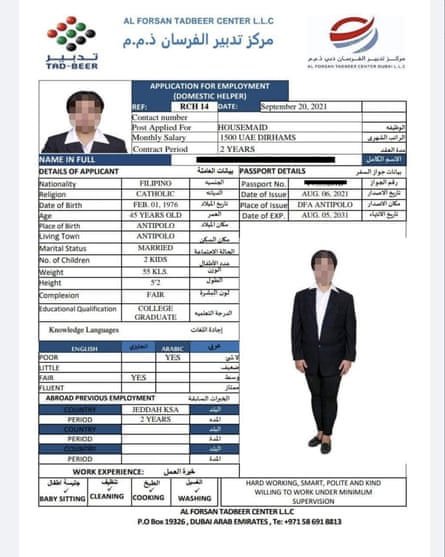

Meanwhile, the Dubai-based Al Forsan Tadbeer agency adverts on Instagram and Facebook list the maid’s names, ages, marital status, passport number, nationality, number of children and weight, and describe their “complexion” in terms such as “fair”, “black”, etc, alongside their photographs.

“There is a close association between dehumanising practices in the recruitment process and wider abuse,” says Lynch. “Put simply, the less that recruitment agents and employers acknowledge the humanity of domestic workers, the less obliged they feel to treat them with dignity and respect.”

A spokesperson for the UAE government told the Guardian: “The UAE maintains a zero-tolerance policy towards workplace abuse. UAE law also prohibits any form of abuse towards employees who undertake workshops regarding their rights and ways to report abuse.

“We conduct comprehensive investigations whenever individuals and/or entities act in such a manner that contravenes UAE legislation. Those that are found to be at fault are held accountable in line with UAE law and legislation.

“UAE labour law mandates that all employees must have paid leave, rest days, medical insurance, accommodation, meals, possession of their personal IDs, and access to free-of-charge legal support. The UAE continues to take active and resolute steps in implementing laws, regulations and monitoring measures to enhance the working conditions of its labour force and address any gap.”

Maids.cc and Al Forsan did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

* Names have been changed to protect the identity of those interviewed.