Hate crimes surge during presidential elections. So far 2020 isn’t any different

Considering trends in 2008 and 2016 elections, authorities are bracing for an expected rise in hate crimes as Election Day nears

Summer is usually a busy time of year for the county’s lead hate-crimes prosecutor. But this year, stay-home orders and isolation had tamped down the usual stack of new hate-crimes reports to review.

That all changed about a month ago. And he isn’t the least bit surprised.

For the record:

10:51 a.m. Nov. 1, 2020An earlier version of this story misstated the nature of the slurs that were allegedly said during an attack on a rabbi.

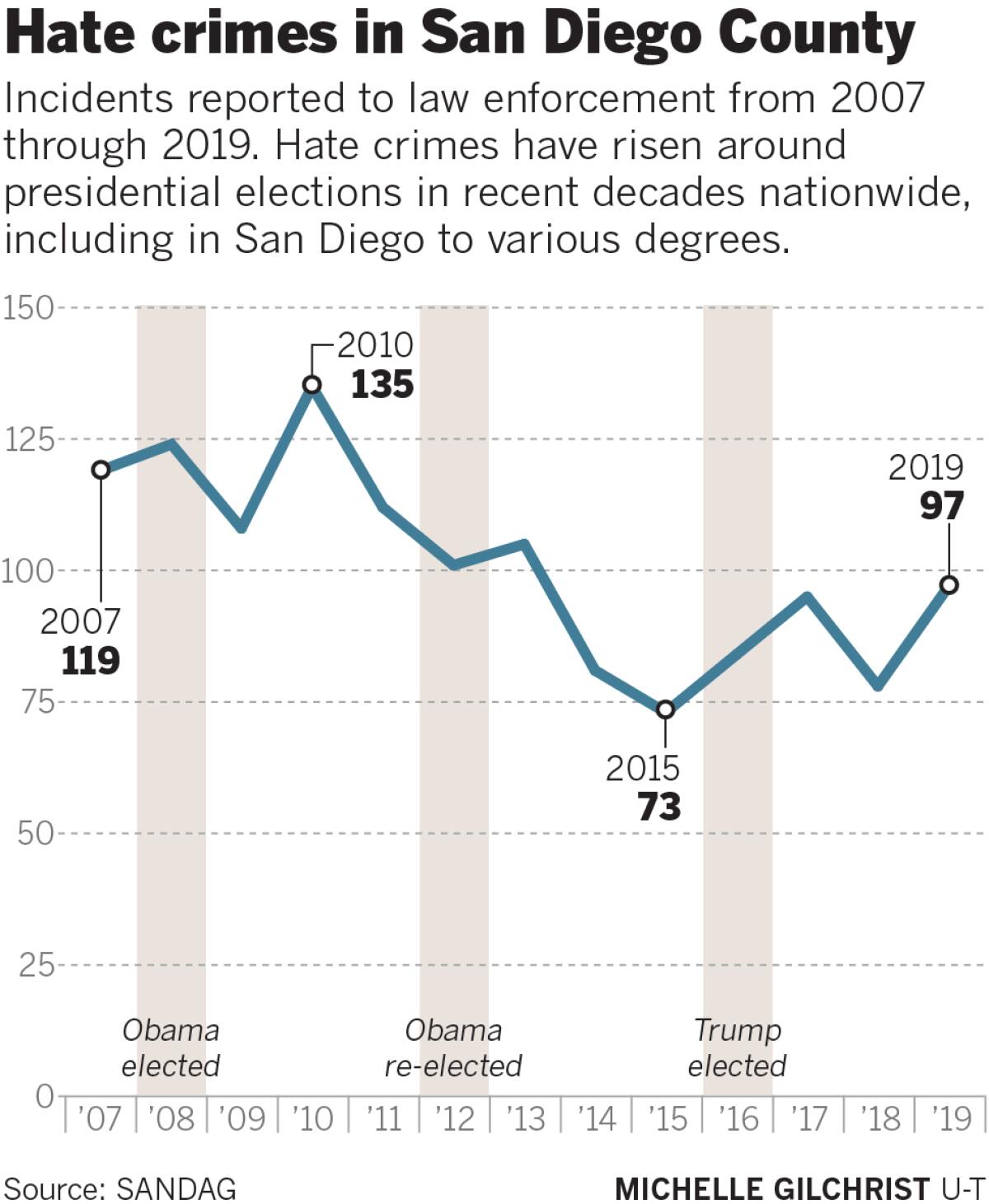

In recent decades, hate crimes have spiked nationally around presidential elections, particularly in the days and weeks immediately before and after Election Day, according to FBI data. The global pandemic does not appear to be stifling the phenomena as we near Nov. 3.

“The last five weeks or so, all the sudden we’ve seen a remarkable increase,” said Deputy District Attorney Leonard Trinh, who handles the bulk of hate-crime prosecutions in San Diego County. “We’ve had six cases submitted in the last three weeks.”

The trend has been documented to some extent during every presidential cycle since the 1990s, when the FBI began keeping data on hate crimes, said professor Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. However, the trend has unfolded differently in various regions.

“When people are getting used to vocalizing their opinions on national politics, it makes it easier to voice opinions about foreigners, people of different religions or sexual orientation.”

— Leonard Trinh, Deputy District Attorney

At a basic level, it doesn’t seem to matter who the candidates are, or who ultimately wins.

The last two presidential transitions of power offer stark examples.

Hate crimes, particularly against Black people, rose in May in 2008, as Barack Obama was poised to take the Democratic nomination in a tight race, said Levin. Hate crime rose again in October, just before the election, as well as after.

When Trump was elected in November 2016, the nation recorded the worst month for hate crimes in more than a decade, with 758 incidents reported.

“Most, but not all, agencies that broke down data by month or quarter showed dramatic increases around election time in November 2016,” according to a report by the Center. Regions considered to be Democratic majorities were among the hardest-hit, according to the report, including New York City, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boston, Washington, D.C., San Jose, Seattle and Phoenix.

“In New York City, the two-week period around the election saw a five-fold increase over the same period the year before,” the Center reported.

In the city of San Diego that year, the number of reported hate crimes doubled from the third to fourth quarter, from six to 12, according to FBI data.

The day after the 2016 election also stands out, with the most hate-crime events reported nationally in more than a decade.

In San Diego, a hate crime was reported that day by a Muslim student at San Diego State University who was robbed in a parking structure. The two men made comments about President-elect Trump and the Muslim community to the woman, who was wearing a hijab, police said.

“We haven’t had a worse day since,” Levin said, in terms of cases reported.

To be prosecuted as a hate crime, there must be a criminal act as well as a motivator of hate that fits the strict requirements under California law.

Hate crime is defined in California as criminal acts against an individual or a group of people because of their perceived race, color, religion, ancestry, national origin, sexual orientation, gender or disability. Targeting someone solely for their political beliefs is not covered under the law.

The motivation of hate must be more than a remote or trivial factor in the crime. That nexus is often supported by comments during the commission of the crime or previous documented aggressions or statements.

The cyclical rise in hate crimes is attributed in part to a spillover effect of the increase in political rhetoric and divisiveness around election cycles, Trinh said.

“When people are getting used to vocalizing their opinions on national politics, it makes it easier to voice opinions about foreigners, people of different religions or sexual orientation,” Trinh said. “There’s something about that season that makes people think it’s more acceptable to express opinions that aren’t as popular, mainstream or politically correct.”

Much of that bias festers on social media, where hate speech is easily normalized. “The more you see it, the more acceptable it becomes to repeat it,” he said.

Forums for people who share similar grievances have exploded online in response to the pandemic and heightened political and social strife, Levin noted. While many forums are not explicitly extremist or racist, they can act as reservoirs that nurture certain biases, hatred and conspiracies. “That can lead them down different rabbit holes,” Levin said.

“What I’m concerned about are the loners who are radicalized rather quickly in an online ecosystem,” he said. “People are experiencing health, psychiatric and economic stress, they are online more at home, and more and more people are angrier.”

What that means for this election cycle — in a year marked by unpredictability — is harder to forecast. But the fresh rise in reported cases, and heightened anxiety over the possibility of disputed election results, increases the expectation that history will repeat itself.

Over the past several weeks, the Anti-Defamation League in San Diego — which tracks hate incidents and extremist activity, particularly against the Jewish community — has been training law enforcement around the county what to watch out for around the election.

“We don’t think there is any cause for panic, but definitely there is a cause for concern,” said Tammy Gillies, ADL’s regional director. She said lately ADL has received more reports of hate incidents, some of which don’t necessarily rise to the level of a crime, such as hate speech.

The recent uptick of hate-crimes cases in San Diego County have run the gamut but are mostly race-based, which is typical around election time, Trinh said.

There have been no arrests yet related to graffiti vandalism at two East County Catholic churches that occurred on Sept. 26. The graffiti was a confusing mix of ideologies — swastikas and White power alongside Black Lives Matter and the name of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden.

On Oct. 10, Rabbi Yonatan Halevy was walking down the sidewalk with his father near his University City synagogue and was punched in the head by a 14-year-old riding his bike, authorities said. The teen spewed slurs, said something about White power and rode off laughing, the rabbi told the Union-Tribune.

Weeks of harassment by the teen and other youth against the rabbi and congregation had preceded the violent encounter, the rabbi said. The teen was arrested on battery and hate-crime charges.

A few days later in a La Jolla park, a man confronted a Latina nanny caring for a 1-year-old baby. He tossed racial slurs her way before trying to kidnap the child, authorities said. A witness intervened, and the man fled into the ocean but was later arrested on charges that included committing a hate crime.

Of the 42 potential hate-crimes cases submitted so far this year by local law enforcement for possible prosecution, 17 people have been charged by the District Attorney’s Office with hate crimes.

There are also federal hate-crime statutes, although they tend to be more narrowly defined. And in some cases, domestic terrorism laws can apply.

“We are prepared if there is an increase in reported hate crimes in the days following the election,” U.S. Attorney Robert Brewer said.

“Past studies show that some people, motivated by anger or frustration, may act out against people they perceive as different or responsible for election results, and those actions may constitute hate crimes.”

Project explores all hate crimes reported between 2014 and 2018, illustrating what kinds of incidents occur in the region and where

However, crimes involving political bias alone are not covered under California or federal hate-crime laws.

Political bias appears to be the motivation for an altercation at an Encinitas street corner in mid-October, when a man approached a Trump supporter selling campaign merchandise. The man tore down the seller’s tent canopy and ran off.

The case remains under investigation, sheriff’s officials said. An arrest could include charges such as vandalism, but it would not be treated as a hate crime if the motivation was purely political.

Understanding the scope of hate crimes both locally and nationally remains difficult, experts say, as many victims don’t come forward. In addition, law enforcement agencies are not required to report hate crimes to the FBI for data analysis. Authorities say there is also indication that many agencies around the country aren’t recognizing hate crimes as such.

In 2018, of the more than 16,000 law enforcement agencies that filed data with the FBI, only 12 percent reported hate crimes occurring in their jurisdictions.

Similarly in California that same year, nearly 300 cities of various sizes reported to the state Department of Justice they had no hate crimes.

In San Diego, authorities have teamed up with community leaders in pushing for more public education around hate crimes and urging victims to report — even when it’s unclear if a crime has been committed.

Hate incidents can quickly escalate against other targets, Trinh said. Documenting such behavior may also prove useful in future prosecutions.

For instance, prosecutors in San Diego were able to build a hate-crime case against a medical student who had beaten a Lyft driver and vandalized his car by showing a 10-year history of police contact in which the man had made derogatory comments against various ethnic and religious groups.

Victims and witnesses are urged to report immediate incidents by calling 911 and to report less urgent matters to local law enforcement non-emergency lines. Reports can also be made to the FBI at (858) 320-1800 or to the District Attorney’s Office at (619) 515-8805 or hatecrimes@sdcda.org.

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.